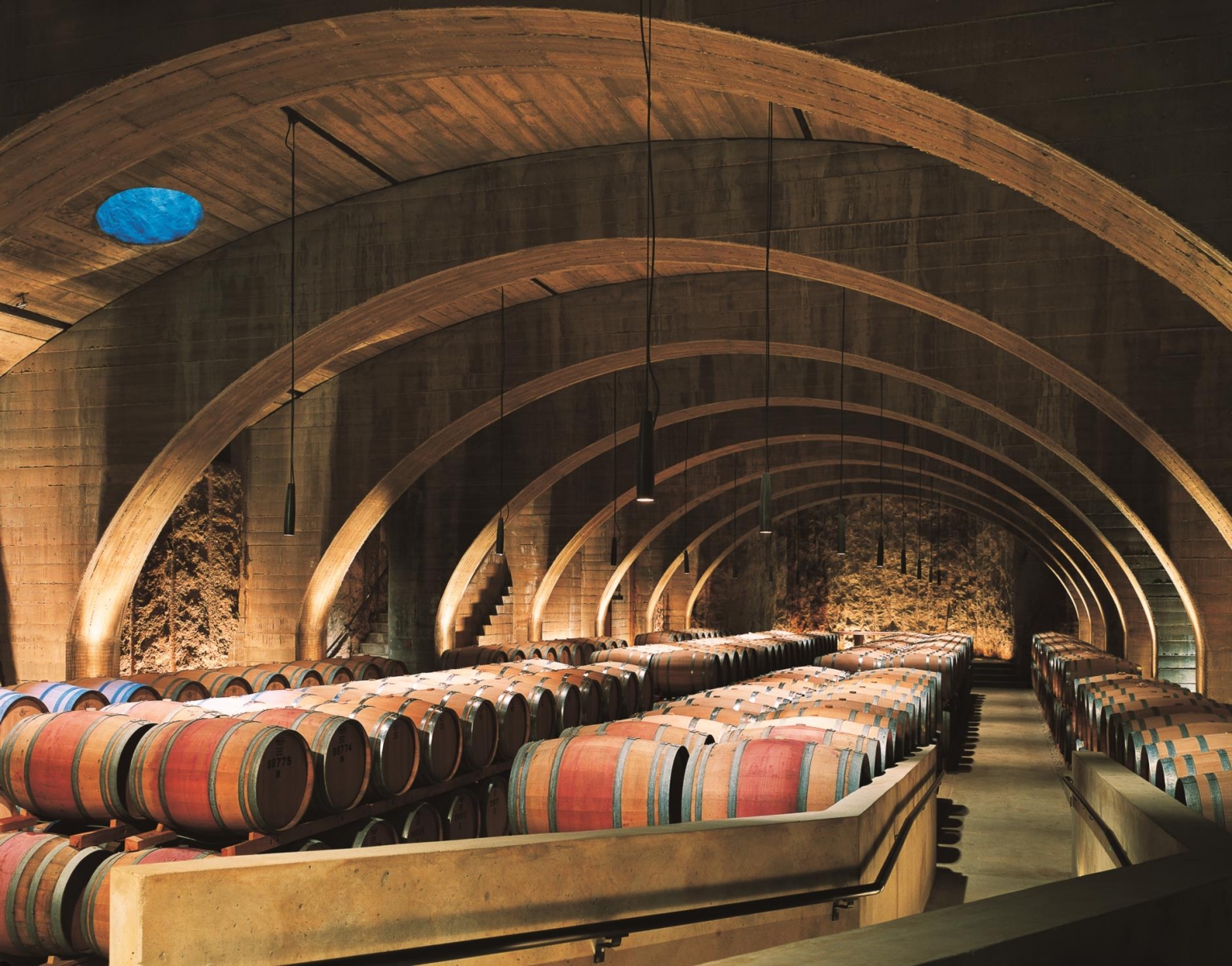

When it rains outside Mission Hill Winery in British Columbia, it pours inside the winery’s massive underground barrel cellar.

That’s a deliberate gesture by architect Tom Kundig, partner in Seattle-based design studio Olson Kundig. He wanted to connect wine lovers to nature across Mission Hill’s 29-acre campus on Okanagan Lake. So whenever rainwater flows from the winery’s 12-story bell tower, it’s directed to an opening in the barrel cellar’s roof.

From there it tumbles, free fall, to splash audibly onto a floor drain composed of cast-in-place concrete blocks. It’s a wakeup call for the five senses: visitors can see the rainwater streaming down; they can hear it hit the concrete; and, if they want, they can reach out to touch it and taste it. But most important, they can smell it.

“It’s the memory-smell connection in the language of the nose,” says Bram Bolwijn, lead sommelier at Mission Hill. “That makes it immortal, and even more personal.”

It’s also pure Kundig. “Tom is a genius who loves architecture,” says the project’s landscape architect, Ron Lovinger. “He has the love of making something beautiful that teaches us about nature, the world, and life. His buildings are alive.”

A MASTER PLAN

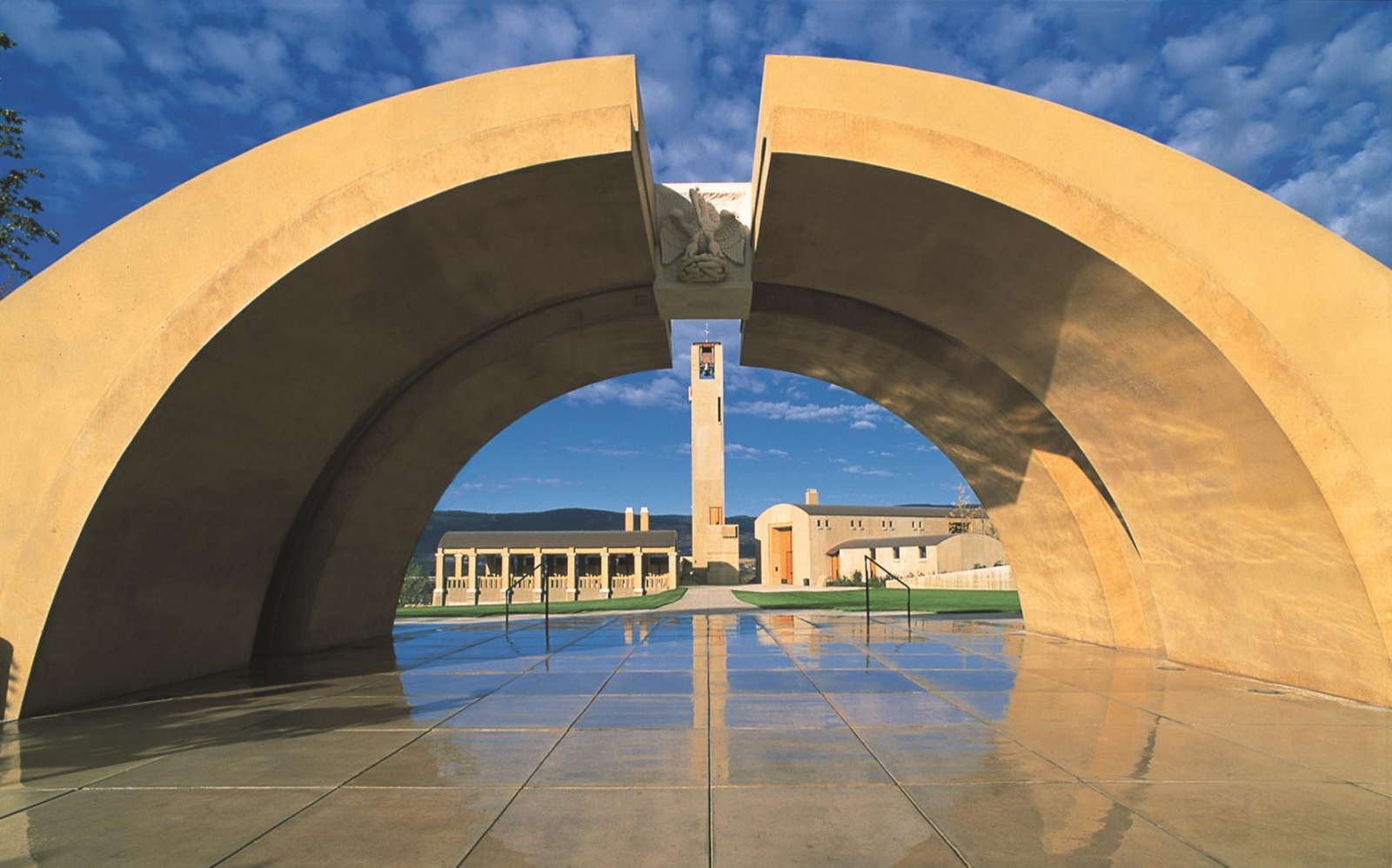

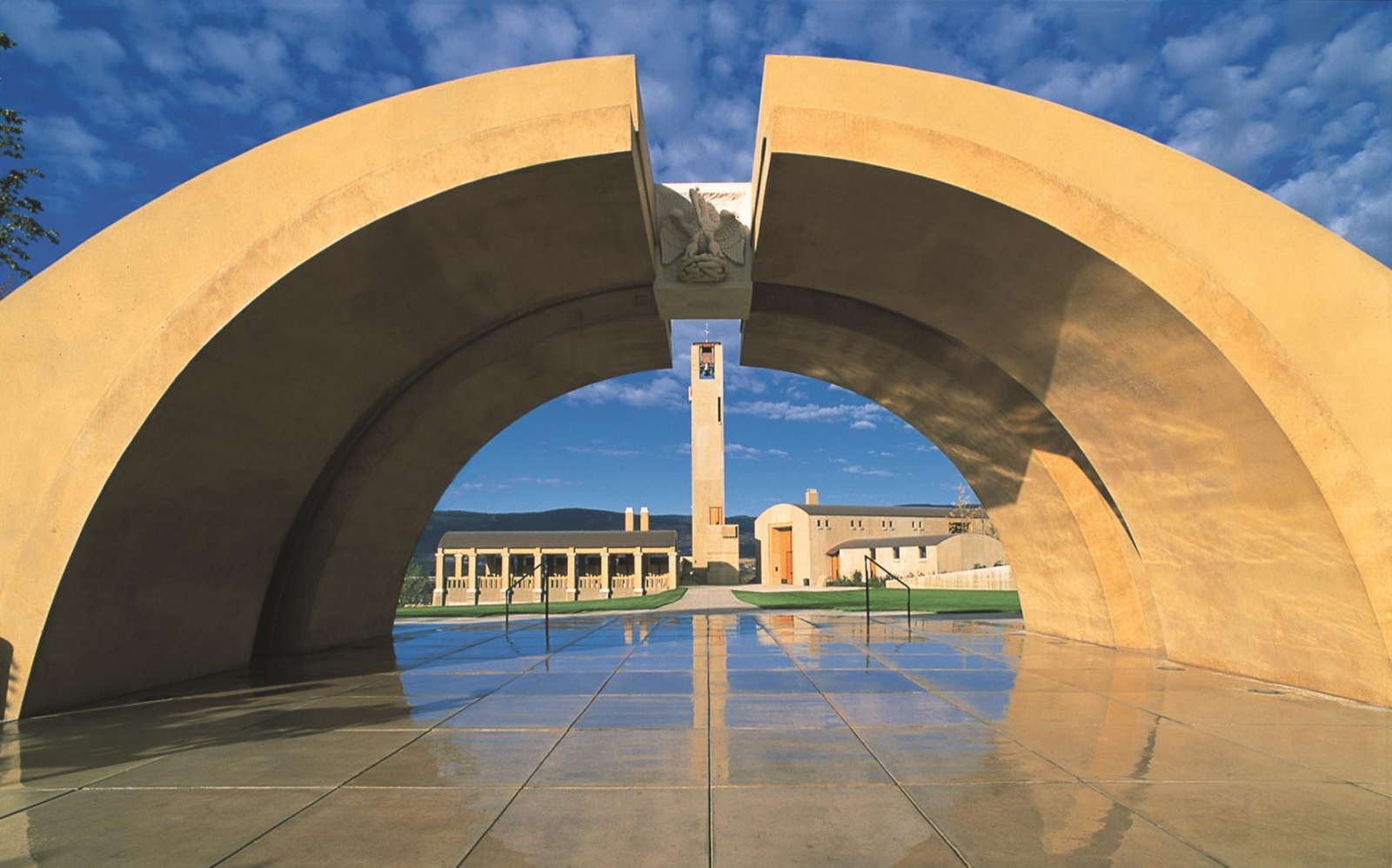

Lovinger worked with Kundig and Mission Hill owner Anthony von Mandl to create a nine-year master plan for the campus’s winery, vineyards, and six structures that began in the mid-1990s. “My intention was to conceptualize a landscape oasis surrounded by the existing buildings,” Lovinger says.

The trio had a geological gem to work with. The site overlooks Lake Okanagan and the surrounding valley. Here, two West Coast tectonic plates are colliding: the thin, desert-like Juan de Fuca plate is slowly slipping under the thicker, granite-laced North American plate. A volcano actively spewed lava here 55 million years ago, and between 10,000 and 16,000 years ago, the Fraser Glacier melted, leaving the lake in its wake.

All that led the team to a master plan that skillfully reveals views of valley and water. “It’s like creating Central Park in New York City—a green, landscaped room in the context of the city,” Lovinger says. “I did that, and Tom created the buildings around it.”

Lovinger’s landscape design emphasizes the view of Lake Okanagan, which forms the context of the winery’s place in nature. “It’s modeled after shakkei, a Japanese term for borrowed scenery,” he says. “You don’t own the lake but it becomes part of your garden.”

The desired effect was to create a lush and verdant refuge in a barren and brown landscape. Lovinger defined a sequence of spaces in a kind of a musical ensemble of gardens. “You walk through the gate and you’re in a green oasis of elements conspiring together to give you a sense of place,” he says. “Then there’s the restaurant and loggia and you see the valley and lake and realize you are somewhere special.”

For his part, von Mandl understood that when people visit a winery, they’re on vacation and want to be away from the noise of civilization and the distraction of mobile devices. He and Kundig visited the great wineries and cathedrals of Europe, which affected Mission Hill’s design. “I was thinking about walking a path and finding a small chapel with a few benches,” von Mandl says. “When you sit there, you’re not thinking about the work or the missed calls or the everyday noise and stress. I wanted you to step out of the everyday world and into a sanctuary that’s all about the timelessness of wine.”

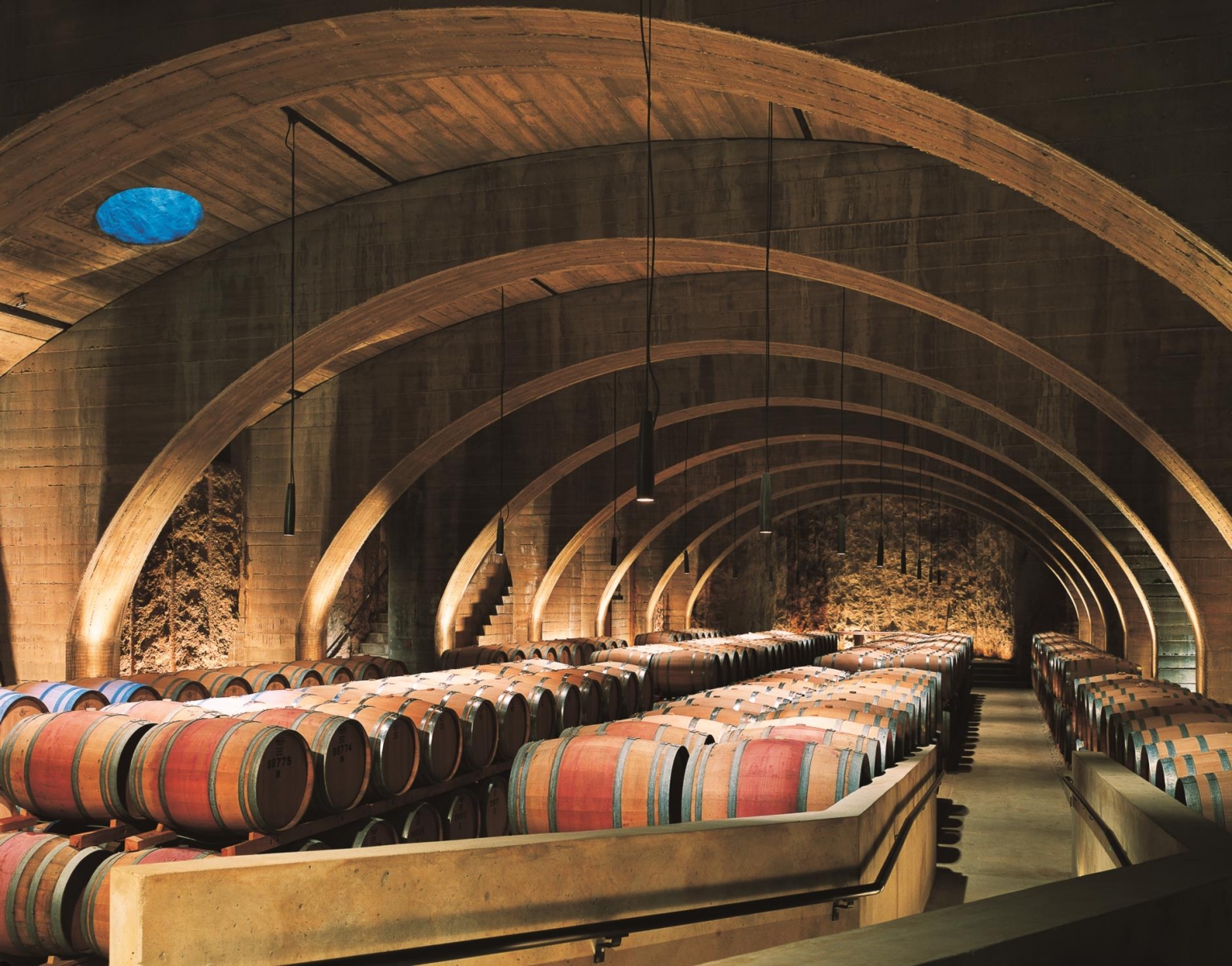

To achieve this vision, the 42-year-old Kundig blasted huge chunks of volcanic rock out of the site below grade, using the loose stone for roadbeds and infill elsewhere on campus. He called for massive panels of poured-in-place concrete in the barrel cellar and elsewhere. “For the interior, we used stone, wood, or plaster to go from the rough nature of concrete to the more refined nature of hospitality,” the architect says.

The result is a vast, harmonic underground temple to winemaking, complete with a raised altar and hushed chapel displaying wine vessels from Etruscan, Greek, Roman, and Chinese cultures. Wine barrels contribute to the architecture—many are filled with Mission Hill’s Oculus, its famed Bordeaux-style red blend whose 2013 vintage earned a score of 92 from Wine Spectator magazine.

Hailing from around the world, 2,500 people visit a day during the summer months and 125,000 pass through every year. And that’s not just because of the wines. The likes of Tony Bennett, Lyle Lovett, and LeAnn Rimes perform outdoor concerts in the amphitheater overlooking the lake and valley. “The concerts are very important to the valley’s social life,” Kundig says. “They extend the Mission Hill brand and the Valley brand, and that’s the agenda Anthony started with.”

It’s a place—a Tuscan village really, made up of 120,000 square feet of buildings—to savor visually and audibly, both indoors and out, created by three like-minded individuals. “I believed that someone had to build an iconic winery architecturally, to give visitors an experience they’d never forget,” von Mandl says. “How many privately financed buildings have you seen that you’d never forget for the rest of your life?”

Von Mandl created his first of that kind on the site overlooking Lake Okanagan but has recently established two more: one on a nearby hillside and another 60 miles south. And Tom Kundig had a hand in designing those, too.

MARTIN’S LANE

In 1994, Mission Hill won the International Wine & Spirit Competition’s Avery Trophy for “Best Chardonnay in the World.” So when von Mandl established Martin’s Lane Winery across Okanagan Lake from Mission Hill, he set out to make the world’s best Pinot Noir there.

He wanted to do that with a gravity-fed winery, a technique adapted from the ancient Romans, who had no mechanical means to move the grape juices. “For the sensitive Pinot Noir grape, we utilize gravity slowly, without pumps,” says Shane Munn, winemaker and general manager at Martin’s Way. “It’s the most efficient way. There are only five moves, from receiving the grapes to putting wine in the bottle, all made with gravity.”

The site, sloping at a 3:12 angle, may be steep for people but not for grapes. “It’s ideal for winemaking—you expose the fruit to the sun like a big solar panel,” Kundig says. “From a fruit-growing perspective, it’s ideal, and from a gravity-fed winemaking perspective, it’s also ideal.”

To accommodate the process, Kundig designed a huge slanting box on the landscape, with a smaller horizontal box that splits it in two. “It’s like a zipper, daylighting at the seam between the horizontal box and the slanting box, offering windows down to the winery,” Kundig says. “It gives light back into the winemaking and hospitality areas.”

His architecture at Martin’s Lane tries to answer as many questions as possible with as few steps as possible. “That’s the intent of good design. How many situations can you resolve with one conceptual move?” he describes. “This is unadorned, rational, and beautiful simultaneously.”

Outside, ponderosa pine, a native Northwest timber, accents the winery’s cladding of Cor-Ten steel, which rusts slowly to a reddish-brown hue. “I grew up with those trees, so that’s a very natural reference,” he says. “And iron oxide is a natural component of the soil, so it slips into the landscape.”

Inside, the fruit and fluid move efficiently from terrace to terrace, gently heating up the fragile Pinot Noir juices. “We tried to squeeze the grapes as little as possible,” he says.

The combined efforts of owner, architect, and winemaker paid off in spades. In 2013, Martin’s Lane won the “World’s Best Pinot Noir” trophy at the Decanter World Wine Awards in London, even as the winery was under construction. “This is a winery about serious winemaking: its best ways and iterations and history and future,” Kundig says. “That’s a different direction from Mission Hill, which has hospitality and community as part of its agenda.”

CHECKMATE

In August 2012, von Mandl looked 60 miles to the south and purchased a winery and vineyards. The property was renamed CheckMate Artisanal Winery, an apt moniker. “It’s a reference to chess itself,” says CheckMate’s winemaker and general manager, Phil McGahan. “There are a lot of similarities between winemaking and chess, especially the need for a plan.”

Von Mandl’s and McGahan’s plans here are in transition today. The existing winery building is still in use, with a Kundig-designed expansion awaiting its building permit. In the meantime, the architect designed a transparent, pop-up tasting room that sits high atop a ridge overlooking Okanagan Valley and provides a framework for viewing vines in the fields.

“I can point to the vineyards where the grapes came from; I can see the mountains and explain their effect on the grapes,” McGahan says. “It also creates an intimate space in which to taste the wine, one that’s elegant and simple.”

Separate from the building where construction will be the norm, the pop-up tasting room occupies prime real estate. “It’s hard to screw up that site and that view,” Kundig says. “But it’s cute as a button and cool, and it establishes a brand.”

The tasting room is essentially an installation. It’s not designed to stay in its current spot permanently. “It will be repurposed at some point down on the highway or as a guest cabin or worker housing,” the architect says. “It’s sort of a modular idea—a truckable idea—to put it on a trailer and pop it back on the ground quickly, without changing the envelope.”

For now, though, it’s all about the experience of tasting the four Merlots and six Chardonnays produced from grapes in the surrounding vineyards, while plans for the new addition get the “full Tom treatment,” according to McGahan.

And one of those wines is likely destined for greatness. “The intention is to do a super-high-expectation Chardonnay out of that winery,” Kundig says.

And why not? The Kundig/von Mandl team has proven itself ably on the world stage over the past few decades. “Anthony and Tom are brilliant,” says landscape architect Ron Lovinger. “Tom is one of the premier architects of our times and Anthony is relentless in finding the perfect person to do what he wants to do.”

A team like that is capable of almost anything—especially producing another world-class Chardonnay from British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT olsonkundig.com, missionhillwinery.com, martinlanewinery.com, and checkmatewinery.com