Key West is about as far south as an American author can go and still live in the states.

For many, it served them well that way for years. “You’re inside the country but far enough away to write about it,” says Arlo Haskell, executive director of the Key West Literary Seminar. “It becomes a kind of self-fulfilling thing – as the years go by, writers live and write here, and then others come here and carry on that dialog. That history draws future writers.”

Poet Wallace Stevens declared it paradise on his first visit in 1922. Ernest Hemingway wrote some of his best fiction there in the 1920s and ‘30s. Unfortunately, the two didn’t see eye-to-eye. In 1936, Stevens broke his hand when he took a swing at Hem’s jaw, then woke up sprawled in the street after the seasoned boxer clipped him with a one-two combo. Stevens later apologized, and went on to win the Pulitzer in 1955 – two years after Hemingway.

Hemingway and wife had pulled into Key West via Cuba in April 1928, expecting to pick up a new car. It wouldn’t arrive for three weeks, so they took up residence in an apartment above the dealership. In the mornings, Hemingway finished up “A Farewell to Arms.” In the afternoons, he explored the island’s fishing legacy.

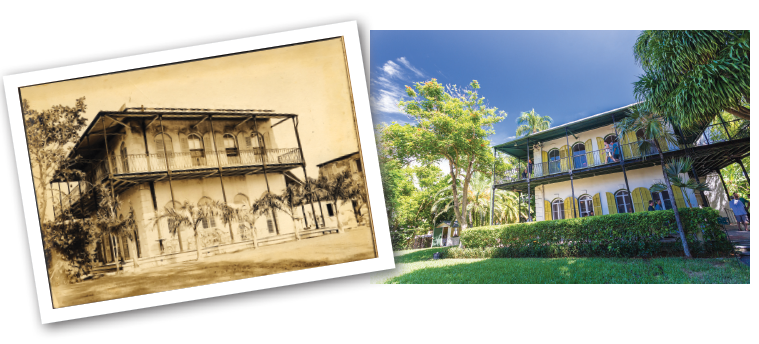

By April 1931, after renting a series of winter houses, they acquired their own at 907 Whitehead Street. “The one they chose was much more grand, and it gets a breeze from down by the ocean,” Haskell says. “And creatively, it was a productive space.”

When they moved in, Hemingway had already published “A Farewell to Arms.” Then came “Green Hills of Africa,”“Death in the Afternoon,” “To Have and Have Not” (set in Key West), and killer short stories like “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro.”

Politics arrived after World War II, when President Harry Truman set up shop at the Little White House on a Key West submarine base. “Every other day, legislature, correspondence and books arrived by courier,” says curator Bob Wolz.

The man who later wrote books on his years in power would host after-dinner poker games, sometimes with the Chief Justice and Speaker of the House. “Everybody got to play who wanted to – and in the living room, the Navy was showing first-run films,” he says.

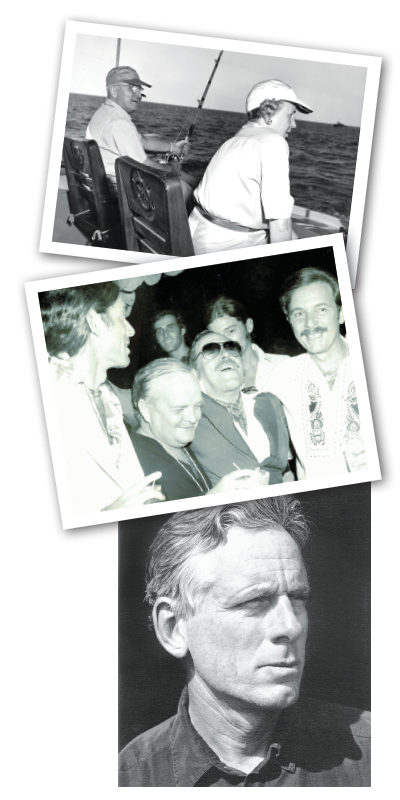

Contemporary author Tom McGuane, who’d fished Key West as a boy with his father, returned in the late 1960s not just for the tarpon, but for the written word and the lifestyle. “It was an easy place to live – it was inexpensive and there was a tremendous amount of juju, shrimpers, bars, hippies, street people, homeless people, dogs and chickens,” he says. “It didn’t feel like the U.S. in those days – it was like the tropics and very appealing.”

Three of his books – “Ninety-Two in the Shade,” “The Bushwhacked Piano” and “Panama” – are set there. He later wrote a screenplay for the first, then oversaw its film direction. “Robert Altman was supposed to direct it and had already scouted the sites,” he says. “He and the producer had a pissing match and Altman quit – and the producer said: ‘You’re going to have to direct it,’ and I did.”

McGuane lived first at 123-125 Ann Street, a block east of wild-and-wooly Duval Street, much of it boarded up. Distracted by the atmosphere, he moved to the relative quiet of 1011 Von Phister. During a lightning-quick series of divorces and marriages, he sold his house, moved to 416 Elizabeth Street, and picked up his pen to write “Panama.”

Not all his time in Key West was productive. “There was so much to do, and the life of your contemporaries was so vivid, and there were the bare feet, and the fishing was great, so it was necessary to develop a rigid little program for writing,” he says. “But in my journal, there’s an entry for 1972 that shows Key West as a completely illiterate winter.”

McGuane wasn’t alone in that. Playwright Tennessee Williams had moved to Key West in the mid-1940s, living in a house at 1431 Duncan Street. “He came here as he was working on ‘A Streetcar Named Desire; and had already made a name for himself,” Haskell says. “He wrote ‘The Rose Tattoo’ here – the Duncan Street house has a terrific rose mosaic in it.”

By the time McGuane met him for dinner in the early 1970s, Williams was anything but prolific. “He was always pretty gaga – I don’t know what drugs he was using,” he says. “He put on ‘Killing Me Softly,’ and played it over and over until he basically passed out in his food.”

But Williams was a magnet for a burst of talent making a beeline to the island, including Truman Capote. “He attracted that sort of coterie of excellent gay writers,” he says. “Capote was much more interesting and fun than the others.”

These days, Key West is jam-packed with tourists tumbling from aircraft and cruise ships, herding onto tour buses and open-air trams, then streaming through the streets by the thousands. To find the real deal, a dedicated sleuth must first conduct some due diligence, then peel back the 21st century’s crude and superficial layers.

“The way to get to it is to pick up McGuane’s “Ninety-Two in the Shade” or Hemingway’s “To Have and Have Not” – and then walk around town and see it through their eyes,” Haskell says.

For those who read, that’s a guaranteed consciousness-raiser.

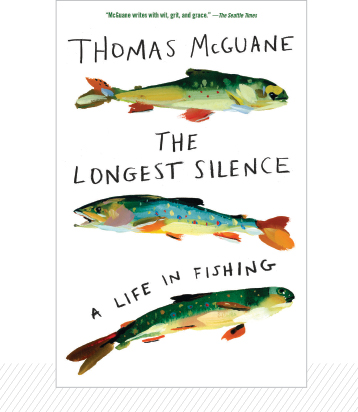

Tom McGuane’s ‘The Longest Silence’

If fishing and writing fit hand-in-glove, Tom McGuane masters that relationship like no one on earth.

He’s proven it again with a revised collection of essays called “The Longest Silence: A Life in Fishing” (2019: Vintage).

“I wanted to include new material from the 15 years since it was first published,” the 79-year-old says.

That meant adding chapters on salmon and tarpon, steelhead and snook – and more. He also offers the reader sensitive and perceptive prose about angling: “Why is it so thrilling? Why is it incomparably thrilling? It’s the contest joined, but also a kind of euphoric admiration and – this is risky – it feels like love. You watch your fish and you are filled with admiration, transported by beauty. Isn’t that love? It was in high school.”

Like his friend, the late poet-novelist Jim Harrison, the man has immortality in him.